I’m finally on summer break, after a long school year during an even longer year, and I return to writing as one returns to an old, neglected friendship. A little timid and sheepish with guilt over the time spent away mingled with the eagerness that only hope and steadfast trust can produce.

I’m playing hooky from the virtual yoga teacher training Jenelle and I are taking together to spend a little time with doublevisionblog this morning because I feel like I have things to say. My thoughts and words feel like they are awakening from a COVID coma, as I strain hard to strengthen their atrophied state, stretching and breathing through the discomfort.

But I’m not alone. My physical therapists come in the form of books, other writer’s stories reminding me of my own, and I read them with the voraciousness of someone who hasn’t eaten in many months. Yes, I’ve read books over the past year for book club and lots of words for work, but there’s something other-worldly that occurs when you get fully lost in a book, and time itself bends , unaware whether 8 or 18 hours have passed as the words pour over you in waves of recognition. In the first 2 weeks of my summer break, my family and I have travelled to 4 states, and I’ve finished 4 books, one for each state, each one aiding in the recovery of a different part of myself.

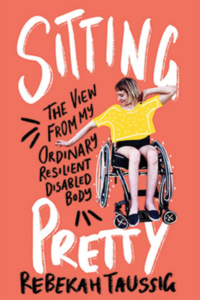

The first book I finished, “Sitting Pretty: The view From My Ordinary, Resilient Disabled Body” aided me in reclamation of my backbone.

The first book I finished, “Sitting Pretty: The view From My Ordinary, Resilient Disabled Body” aided me in reclamation of my backbone.

This memoir is a NYT bestseller written by a disability advocate living with paralysis. The book was actually recommended by a good friend from the “Daring Sisters” retreats Jenelle and I have attended and is written by her cousin, Rebecca Taussig. It is a collection of essays about her experiences growing up with a disability and the complications of kindness and charity, intimacy and ableism. If these sound like heavy, somewhat-depressing topics that aren’t exactly light summer reading, that is half true. As I read Rebecca’s words, I grappled alongside her over the complexities of living in a body “that has been sent to the margins”, as she writes in her dedication. And yet her coming-of-age stories with references to 80s and 90s teen girl icons like Christy Turlington and teen magazines weave in a lightness that had me nodding, smiling and chuckling to myself at times.

I actually began reading her book back in February, and I quickly discovered that this would not be a book I devoured in one sitting, that it was not meant to be inhaled like a beach read, but one meant to be parsed out, one layer at a time. I somehow knew that I must wait to finish this book when I would have time and space to process, which for me as a teacher is usually during summer break.

While our disabilities are vastly different, I was struck by how she put words to many of the experiences I’ve had both growing up and as an adult experiencing life in a disabled body. Her words on shame in chapter 1 resonate so deeply that I can’t decide whether I am more comforted or disturbed by the fact that shame seems to be at the center of suffering for a person living with a disability. Rebecca writes,

“In the midst of my verbal wandering I inevitably reached for the word shame, the box where I had lived for so very long. The box I still find myself tumbling back into with less provocation than I’d like to admit. This is the shame that attaches so easily to a body that doesn’t fit. The shame that buds, blossoms and blooms when you believe that your existence is a burden, a blemish on the well-oiled machine of society.”

While Jenelle and I have written and spoken about shame quite a bit, I didn’t realize how much I still struggle with it until I was spending a quiet, balmy California evening with a good friend, and several buried stories found their way to the surface, to my surprise, as the tears followed. Why did the stories choose this moment to rise to the surface? Why did I feel comfortable sharing them with this friend? Why did I feel in my being that this friend really “got it” despite the fact that she herself does not have vision loss or a disability?

I think the answer is “access intimacy”, a term coined by another disability rights activist, Mia Mingus. On her blog, “Leaving Evidence”, in a 2011 post she described access intimacy as an “elusive, hard-to-describe feeling when someone else gets your access needs and a sense of comfort that your entire, disabled self feels”. I heard Mia go into more detail in a talk, and she says that you can feel access intimacy with strangers or those close with you and that you can have close family members and friends with whom you do not experience access intimacy. For someone with a disabled body, this description helps explain so many experiences I’ve felt relationally over the years. It explains why I felt such a devastating void when a friend planned a bike ride in Chicago for her birthday and didn’t invite me because she said “it would have been hard for you” without considering a tandem or another way for me to participate. It explains why a recent shopping trip with friends to Marshall’s was hilarious and fun while a similar trip with different friends felt isolating. It also explains the hollow feeling in my gut when hearing a friend say that my life isn’t any different from a fully sighted persons because blindness does not define me.

I can hear readers remarking, “but wait, I thought vision loss doesn’t define you?” I understand the confusion, and that’s why I am grateful to Rebecca for diving into this complex conversation.

This is not to say people with whom we experience access intimacy necessarily understand the intricacies of disability or its webbed relationship with shame. On the contrary, my SoCal bestie asked lots of questions the evening I clumsily attempted to explain the social constructs that I believe lead to ableism and shame.

Access intimacy is the difference between asking “need an arm?” when you see me struggling versus grabbing my hand and steering me like an object, yet it is also not a scripted way of relating to someone with a disability.

It is in the posture. It is in the ask.

While it’s not a term I saw in “Sitting Pretty”, the concept is woven in, and Rebecca’s stories of ableism and the complications of kindness helped me understand why someone jumping up from their dinner at a nearby cafe to escort me across the street— a street I crossed every day for years quite capably when no one was present— made me feel more harassed than helped but then guilty for not feeling grateful.

Rebecca’s words about kindness offer a much-needed perspective to my feelings. She writes: “Maybe it’s because so many of us claim kindness as one of the most important qualities humans can possess. Disrupting our understanding of kindness is a direct threat to our sense of self and the world around us. But as a veteran ‘kindness magnet’ I found people’s attempts to ‘be kind’ could be anything from healing to humiliating, helpful to traumatic. It’s complicated”.

When Rebecca told the story of the woman asking to pray for her in the cafe, I was instantly in the Aliso Viejo Barnes and Noble 5 years ago. I am shopping with my daughter, Lucy, 10 at the time, and we are picking out Calico Critters for her little sister’s birthday and perusing Babysitter Club graphic novels. We are smitten with the velvety squirrel family and immersed in our own world of mother-daughter time, unaware that a stranger has been eyeing us and is making her way toward us.

“Excuse me,” she says, and I turn to let her pass, thinking perhaps I’m in her way. “I feel the Lord prompting me to pray over you.” I must look confused. “For your eyes to be healed,” she says, indicating my cane, which I’d forgotten I even had been using. I can’t remember why my guide dog wasn’t with me, which usually prevents these types of scenarios for some reason.

My stomach tightens and I feel “no” but I heard myself saying “Um, sure, okay”. She places her hands on me and says words I cannot remember because I am too hot with embarrassment. For the woman? Myself? Lucy?

After she says “Amen”, she says “I hope you know how beautiful your daughter is” in a sad tone, like she is telling me something about my own flesh and blood that I am not privy to because my eyes don’t work like hers. It is only now, 5 years later, after reading Rebecca’s story, that I am fully processing this story, and the absurdity of the facts are alarming.

I teach social/emotional skills to parents and students for a living. I imagine a family coming to me today with this scenario: A stranger asks to place hands on a mother and say words that make her feel uncomfortable. Afterwards, when the child asks the mom if that felt weird and the mom says “yes it did, but sometimes you give someone a gift when you allow them to feel kind”. This is essentially what happened at Barnes and Noble, and my actions made sense at the time. If a parent came to me with this scenario today, I’d have a discussion with them about boundaries and how we model them for our children.

That explanation seemed to satisfy me 5 years ago, but recounting it now, hot tears say otherwise. I was basically telling my daughter that it’s okay to allow someone to do something you’re uncomfortable with if it makes them feel good. This is not a message I want to pass along to the next generation. I wondered how much Lucy remembered this Barnes and Noble experience, so I asked her.

“Yes, of course I remember that. It was so awkward, mom,”

“Yes it was. Do you remember the conversation we had afterwards?”

“Yes,” she says, only she remembers a part that I didn’t.

“I asked you if you would want to be healed and if you wish you never had RP.” I find it incredible that a 10-year-old somehow knows to ask the question that the woman who prayed for me should have asked before she asserted her need for my healing onto me.

“How did I answer you?” I ask, vaguely remembering the conversation and truly curious how I answered.

“You said that without RP you wouldn’t have Roja and a lot of your closest friends. You said it made you more compassionate.”

These statements still ring true for me, though I am now very aware of the “both and” thinking I’ve adopted. I still check on clinical trials and would love to stop the degeneration of vision. And I would never give up Roja or the friendships I’ve formed with others who have vision loss. Both can be true.

I understand that this story alone may be seen through different frameworks for my readers. Some of you may cringe with me as you read, and others may wonder what the big deal is. So you allowed someone to pray for you… weren’t the intentions behind the woman’s actions good? Both responses are valid, and regardless of where you find yourself in this conversation, I encourage you to explore the nuances of ableism by reading the essays in “Sitting Pretty”. Rebecca dives into the conversation with much more depth and insight. I’ll leave you with a quote from her:

“And when we’re focused on alleviating our own uneasiness, we’re not really looking into the face of the person whose hand we’ve grabbed. That feeling of discomfort is worth reflection. It’s a red flag signaling something needs attention. But a gut reaction to discomfort can do more harm than good. Thoughtful reactions take time and reflection.”

Wow! What a gift this is.

What a gift YOU are, my surprise baby Joy!

Thanks for sharing this with us Joy! You have given me a lot to think about, thank you! ❤️❤️❤️

Hey Joy, so helpful for you to articulate this and share it. I know it is different but when I was a young mom with a husband hospitalized I experienced a LOT of help. And much of it was a miraculous and impressive lifeline. But it was really challenging and continues to be challenging to receive self centered, unwanted, uninvited help. When it was offered with presumption more than invitation. It often left me feeling violated. And occasionally others expressed indignation if I said no thank you. I think our culture teaches cookie cutter kindness that never learns the power of consent and doesn’t end up being truly kind at all. It IS nuanced and complicated and difficult to learn and therefore it is undertaught (—I know that’s not a word but it makes sense here). The more articulate people like you teach it, spread it, clarify it it will apply to learning advocacy and allyship (?) in every other regard as well! Thank you for teaching and leading me!

What a insightful helpful read! Thanks dear Joy. As always you live into your name and bring others there with you 💙

Joy, poignantly written with an intimate, yet powerful message. You are a gifted writer and because you shared your vulnerability, I believe I understand your experiences and perspective more fully. Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I am grateful.

Recognizing, naming, and feeling/processing the trauma I’ve experienced both in and outside of the church from “well intentioned” people is an ongoing process. What may have seemed like little moments to some, (even recently with the passing of my father due to covid and people’s ignorant comments about the hoax of a deadly virus) have been huge to me and stuck with me in painful, resentment-inducing ways. I so appreciate your insight and willingness to be authentic in sharing, Joy. I wish I knew more about the work you are doing now as it sounds right up my alley! I hope you, Ben, and the girls are well.

As usual joy, very insightful! Thank you so much for all you do and for all you write❤️